The enduring legacy of Paul Robeson: from Hollywood exile to timeless resonance

Bold statements and profound impact

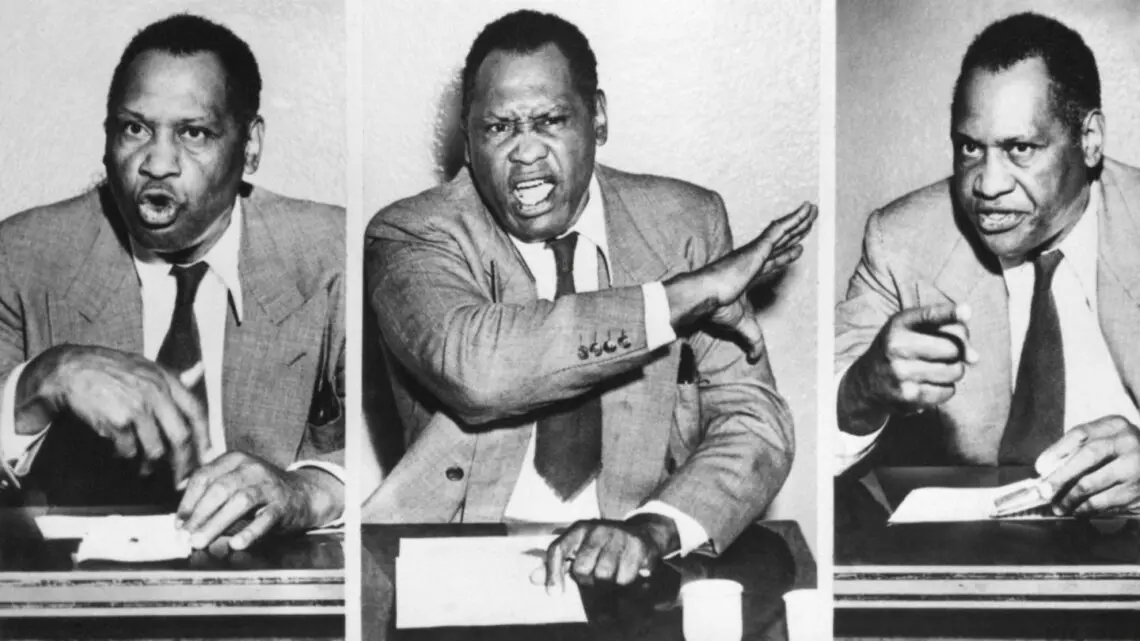

Few figures in American cultural history resonate as profoundly as Paul Robeson. Once at the zenith of fame as an unparalleled artist-activist, he charted an extraordinary trajectory through the main events of his era: the Jazz Age, the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War. Robeson was not merely present during these transformative periods; he exerted a tremendous influence across myriad platforms—from the stage to records, concerts, radio, and film.

A titanic talent in a tumultuous era

Born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, NJ, Robeson’s life was steeped in the potent mix of educational ambition and religious devotion, hallmarks of his upbringing by a former enslaved person turned minister and a teacher mother. Robeson’s academic and athletic prowess were evident early on at Rutgers College, where his footprint was indelible. By 1919, he not only emerged as a star athlete with eleven varsity letters but also as an academic trailblazer, graduating with a Phi Beta Kappa honor.

He continued his scholarly endeavors at Columbia University Law School, earning his degree in 1923, despite never actively practicing law. It was during this period that Robeson encountered and married Eslanda (“Essie”) Good, who would become his life’s partner, manager, and collaborator. Her encouragement was pivotal, steering him towards what would become an illustrious career in the arts.

Trailblazer on stage and screen

Robeson had long sung and acted, but it was the Provincetown Players theater group that provided a significant leap in his career. By 1924, he was tapped for the lead in Eugene O’Neill’s controversial play All God’s Chillun Got Wings. A year later, he cemented his status as a leading actor with his performance in The Emperor Jones.

Though Robeson’s talents merited a prominent place in Hollywood, the industry’s limited roles for a Black man unwilling to conform to stereotypes stymied his film career. His breakthrough came with Body and Soul (1925), directed by Oscar Micheaux, where he played dual roles that showcased his range. Yet, mainstream recognition eluded him, as race films were relegated to segregated theaters.

Robeson’s next significant silver screen opportunity arose with the 1933 release of The Emperor Jones, in which he reprised the role that had brought him acclaim on stage. This film, though steeped in dated racial dynamics, was a landmark in its representation of potent Black masculinity. Notably, Robeson’s commanding presence in the chain gang sequence remains unforgettable.

Unrivaled in music and activism

Robeson’s Hollywood appearances may have been limited, but his impact on stage and in music was formidable. He became renowned for his portrayal of Joe in the musical Show Boat (1936), where his rendition of “Ol’ Man River” became iconic. By then, Robeson had carved a niche, infusing his performances with the political convictions that gave new life to his roles. For Robeson, art and activism were inseparable.

As the Great Depression ravaged America and racial tensions soared, Robeson’s political ideology veered sharply left. He became an ardent supporter of the Soviet Union and an indefatigable advocate for labor rights, anti-fascism, and civil rights for Black Americans. His revised lyrics to “Ol’ Man River” reflected his steadfast commitment to struggle and resistance.

Redefining boundaries in a segregated industry

Though Hollywood did not fully embrace Robeson, British cinema welcomed him. Throughout the 1930s, he starred in several British productions, including Sanders of the River (1935), The Song of Freedom (1936), and The Proud Valley (1940). These films allowed him greater creative freedom, although they might have received little attention in the United States.

Robeson’s charismatic performances in Britain contrasted sharply with the limited opportunities afforded to him in Hollywood, underscoring the racial barriers prevalent in American cinema. Despite these challenges, his body of work remains a testament to his talent and resilience.

The blacklist era: a resilient spirit

The onset of the Cold War ushered in an era of McCarthyism, when being labeled a communist or even a sympathizer could derail careers. For Robeson, the repercussions were severe. Despite his groundbreaking contributions to American cultural life, he faced blacklisting and ostracism. Yet, his unwavering commitment to social justice and his prolific artistic output continued to inspire generations.

Robeson’s struggles during this period highlighted the tense intersection of politics and art. His legacy, however, extends far beyond his blacklisting. As a forerunner of the Civil Rights Movement and a trailblazer in the arts, Robeson’s influence persists, resonating with new generations of activists and artists.

Celebrating a multifaceted legacy

Paul Robeson’s life encapsulates the struggle, triumph, and relentless pursuit of justice that defined much of 20th-century America. His legacy, etched in the annals of history, continues to inspire. Whether through his commanding performances on stage and screen or his tireless advocacy for equality, Robeson’s contributions to culture and society remain unparalleled.

For those interested in exploring his filmography, visit The Emperor Jones and Show Boat to witness the indomitable spirit of a man who transcended barriers and championed change.

Share this remarkable history with friends and follow our journey as we continue to delve into the stories of other influential figures who have shaped our world.## Paul Robeson: an artist’s journey through persecution and perseverance

Dance with the times

Emerging from the rich cultural and historical tapestry of early 20th-century America, Paul Robeson stands as a monumental figure whose arts and activism have left an indelible mark. Actor, singer, and political activist, Robeson navigated through periods of profound change, leveraging his talents to speak out against oppression and injustice—qualities that eventually saw him blacklisted during Hollywood’s McCarthy era.

Rising star from humble beginnings

Born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, NJ, to a former enslaved person turned minister and a teacher, Robeson’s upbringing was marinated in the virtues of education and faith. Defying the odds, he excelled both academically and athletically at Rutgers College, earning not just a Phi Beta Kappa but also eleven varsity letters.

Continuing his academic journey, Robeson attended Columbia University Law School, obtaining his degree in 1923. Although he never practiced law, this period defined his future as he met Eslanda (“Essie”) Good, who would become his wife and lifelong collaborator, steering him towards his artistic calling.

Breaking new ground in theater

Encouraged by Essie, Robeson’s early artistic endeavors brought him to the Provincetown Players. There, in 1924, he stunned audiences with his lead role in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings, tackling controversial themes of miscegenation. His performance in the 1925 revival of O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones solidified his reputation.

While Hollywood scarcely offered him roles that matched his talent, Robeson found more significant opportunities in London, breaking racial barriers by performing as Othello in 1930— a role he would reprise in groundbreaking performances in America in 1943.

Cinema’s reluctant revolutionary

Robeson’s early forays into cinema included the trailblazing Body and Soul (1925), directed by Oscar Micheaux. His dual role demonstrated his immense range, yet mainstream recognition remained elusive. The film’s reception was confined mostly to segregated “race theaters.”

A more notable entry was The Emperor Jones (1933), where his portrayal was powerful and enduring. However, his most memorable screen role came with the 1936 film Show Boat, showcasing his iconic rendition of “Ol’ Man River,” a song that became a hallmark of his career.

Activism and the sting of exile

With the advent of World War II, Robeson’s ethos aligned with national interests, making him an advocate for war bonds, and fronting government-sanctioned programs. Yet, the conclusion of the war quickly marked a chilling transition; the Cold War’s onset saw Robeson labeled as a Soviet sympathizer, bringing scrutiny from figures like J. Edgar Hoover.

His unflinching commitment to Communist ideals drew severe backlash. In 1949, his remarks at a peace conference in Paris against American racial injustice drove home the point further, leading to intense media scrutiny and escalating tensions back home.

The Peekskill riots: a pivotal moment

Robeson’s activism reached a crescendo with the Peekskill riots of 1949. A planned concert to support the Civil Rights Congress drew violent protests and symbolized the nation’s racial and political schisms. Despite violent opposition, Robeson stood firm, delivering a heartfelt performance encircled by security.

The post-concert chaos received extensive media coverage. The unrest was a stark reminder of the fierce resistance against his message of racial equality and labor rights. The incident notably marked one of the rare instances where Robeson’s image was broadcast during the blacklist era.

Robeson’s TV blacklisting: the unseen artist

As television emerged as a dominant medium, Robeson faced an informal but ironclad ban, one catalyzed by an attempted appearance on Today with Mrs. Roosevelt in 1950. The public outcry led NBC to cancel his appearance, illustrating the pervasive fear of Communist influence on American airwaves.

Robeson’s blacklisting lasted for a staggering 25 years, only lifting posthumously. During this period, his absence on television was a stark reflection of the fraught lines between artistry and political ideology.

Legacy of a multifaceted icon

Paul Robeson’s legacy is etched into the history of 20th-century American culture; his life’s arc from a celebrated artist to a blacklisted outcast underscores the tensions at the intersection of race, politics, and the arts. His contributions continue to inspire and challenge new generations, embodying the enduring struggle for justice and equality.

Discover more about his profound impact by exploring his filmography and insightful performances. Share the story of Paul Robeson and follow our updates for more on influential figures who have reshaped the landscape of art and activism.# Paul Robeson: American luminary, exiled voice

A unique journey through art and activism

Paul Robeson remains one of the most compelling figures in American cultural history. Known for his commanding stage presence, mellifluous voice, and unwavering commitment to social justice, Robeson’s career transcended mere entertainment. Yet, his path was fraught with adversity, particularly during the McCarthy era, when his political beliefs led to his blacklisting from Hollywood and, ultimately, American television.

The making of a Renaissance man

Born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, NJ, Robeson was raised in an environment that emphasized the value of education and religious faith. His father, a former enslaved person turned minister, and his mother, a teacher, imbued him with resilience and ambition. These qualities shone brightly during his time at Rutgers College, where he became an All-American athlete and a Phi Beta Kappa scholar, earning eleven varsity letters across multiple sports.

Continuing his academic trajectory at Columbia University Law School, Robeson completed his law degree in 1923 but shortly thereafter shifted his focus to the arts—encouraged by his wife Eslanda (“Essie”) Good, a profoundly supportive partner. This decision catapulted him into a career that spanned music, theater, and film.

Breaking barriers in theater and cinema

Robeson’s initial foray into professional acting began with the Provincetown Players theater group. His landmark role in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings in 1924, followed by The Emperor Jones in 1925, established him as a preeminent actor willing to tackle challenging and controversial subjects.

Despite his success in theater, Hollywood offered limited and often stereotypical roles for Black actors. However, Robeson’s portrayal in Body and Soul (1925), directed by Oscar Micheaux, showcased his versatile talent. This film marked a crucial stepping stone, affirming his skill but also highlighting the racial limitations within the industry. Robeson later starred in the film adaptation of The Emperor Jones (1933), a role that resonated both for its depth and its daring portrayal of Black masculinity.

His most celebrated film performance came in the 1936 adaptation of the musical Show Boat, where his rendition of “Ol’ Man River” became a timeless anthem. Robeson’s ability to transform the song’s lyrics to reflect his social and political convictions spoke volumes about his talent and activism.

The intersection of art and activism

World War II saw Robeson’s artistry align with national interest, as he participated in patriotic efforts such as war bond drives and government-approved radio programs. Yet, with the war’s end and the advent of the Cold War, his outspoken support for the Soviet Union and civil rights suddenly positioned him as an enemy within.

The Peekskill riots of 1949 epitomized the volatile reaction to Robeson’s activism. A concert organized for the benefit of the Civil Rights Congress in Peekskill, NY, was met with violent protests by anticommunist agitators. Robeson remained resolute, performing despite threats and subsequently becoming a symbol of defiance and courage against racial and political oppression.

Television blacklisting: silencing a powerful voice

As television emerged as a dominant medium, Robeson encountered systemic exclusion. When it was announced that he would appear on Today with Mrs. Roosevelt in 1950, public outcry led to the cancellation of his appearance. This incident marked the beginning of his long-lasting television ban, a trend that Red Channels—a report on Communist influence in radio and television—further institutionalized.

Robeson’s fidelity to his political beliefs came at a steep price. His passport was revoked in 1950, effectively confining him to the United States. Attempts to regain it were consistently thwarted, primarily due to his refusal to denounce communism.

The enduring struggle for justice

Robeson’s confrontation with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1956 underscored his defiant stance. Unlike many who appeared before the committee, Robeson did not cower. His words—“You are the non-patriots and you are the un-Americans”—echoed the sentiments of many marginalized voices, yet his outspokenness further cemented his blacklisting.

A modicum of justice arrived in 1958 when the U.S. Supreme Court curtailed the federal government’s ability to confiscate passports. Finally able to travel, Robeson received a hero’s welcome in the UK, embarking on a triumphant tour, although his American television ban persisted.

A legacy eclipsed by ‘what might have been’

Paul Robeson’s later years were marked by health issues and a gradual retreat from public life. Although he passed away in 1976, the lingering impact of his blacklist was felt even posthumously. Controversies around awarding him a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame and the backlash against a Broadway show about him reflect the complex legacy he left behind.

Today, Robeson is revered as a monumental figure in cultural and political history. His life serves as an evocative reminder of the perils of political dissent and the enduring power of an artist committed to justice. The work he couldn’t complete during his career remains a poignant what-if in the annals of American art and activism.

For those eager to delve deeper into Robeson’s remarkable contributions, consider experiencing his performances firsthand:

Share this powerful narrative and stay tuned for more explorations into the lives of transformative figures who have helped shape our collective history.

Italian

Italian