Like a lot of people, I first saw Billy Preston in “Let It Be,” where his luscious electric-keyboard noodlings provided the sweet center to songs like “Don’t Let Me Down” and “Get Back.” But it wasn’t until “The Concert for Bangla Desh,” George Harrison’s trend-setting rock-concert movie from 1972, that I registered who Billy Preston really was. For most of that Madison Square Garden benefit concert, Preston was in the background, tickling those plugged-in ivories. But then, introduced by Harrison, he performed the single he’d recorded in 1969 for Apple Records, “That’s the Way God Planned It.” It stood out from the rest of the show as dramatically — and magnificently — as Sly Stone’s performance of “I Want to Take You Higher” did from Woodstock.

The sound of a holy organ rang out, and the camera zoomed in on a stylish-looking man in a big wool cap and a Billy Dee Williams mustache, with a handsome gap-toothed grin and a gleam of reverence. He began to sing (“Why can’t we be humble, like the good lord said…”), and it sounded like a hymn, which is just what it was: a rock ‘n’ roll hymn. The lyrics lifted you up, and Preston caressed each cadence as if he were leading a gospel choir. In 1971, how many pop songs could you name that had “God” in the title? (There was “God Only Knows” and…that’s about it.)

Popular on Variety Yet as he launched into the chorus, with its delicate descending chords, its bass line following in tandem, at least until the climax, when that bass began to walk around like it had a mind of its own, you could feel the song start to…ascend. Preston, rocking back and forth, tilting his head with rapture, the notes pouring out of him like sun-dappled honey, was the only Black performer on that stage, and he was offering what amounted, in the rock world, to a radical message: that God was here. As the song picked up speed in the gospel tradition, Preston, moved by the spirit he was conjuring, got up from his keyboard and began to dance, jangling his arms, his legs just about levitating. It was an ecstatic dance, one that seemed to erupt right out of him, as if he couldn’t stop himself.

Paris Barclay’s eye-opening documentary “Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It” opens with that sequence, and it’s cathartic to see it again. “The Concert for Bangla Desh” had three highlights: Bob Dylan’s extraordinary set; the way that George Harrison, in what felt like one of the coolest things I’d ever seen when I was 13, took his exit from the stage right in the middle of the final rave-up of the song “Bangla Desh”; and Billy Preston’s performance. You watched it and thought, “Who is this man?” And also, “I must see more.”

But as the documentary reveals, Billy Preston was an elusive figure — ebullient and all there, and also hidden and mysterious. His career was like that too. He was a genius session musician who worked with Little Richard, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Sly Stone, the Rolling Stones, and, of course, the Beatles. During the “Get Back” sessions, he was effectively added to the Beatles, which was unheard of. (In a scrapbook montage near the beginning of the film, we see a magazine headline that reads, “The Fifth Beatle Is a Brother.”)

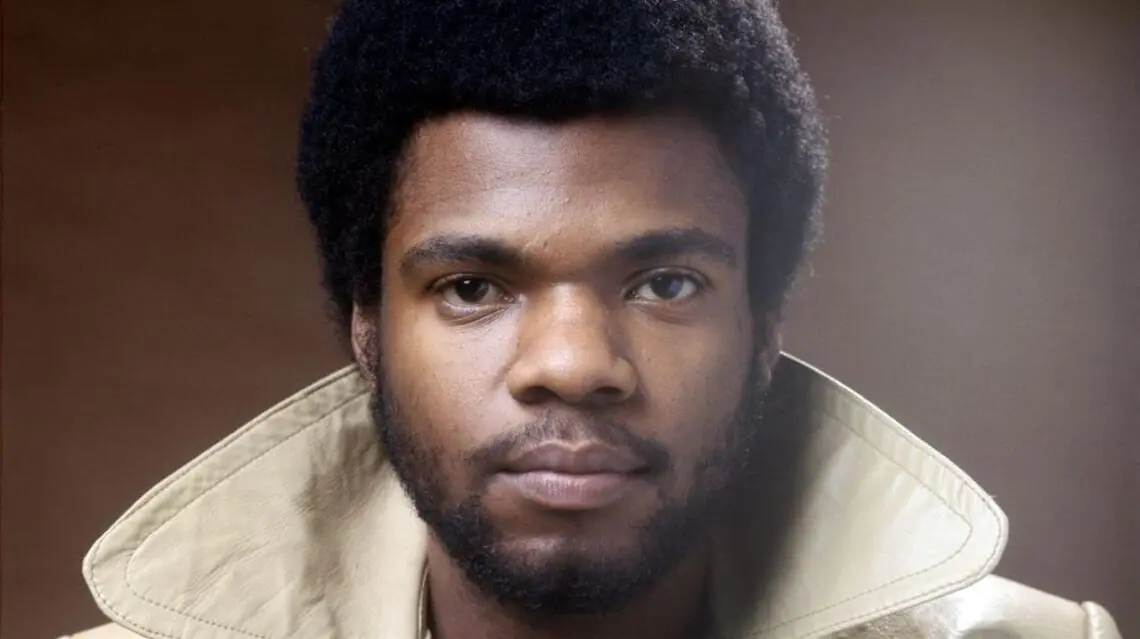

As the ’70s went on, Preston put out a handful of pop-funk singles that people still remember fondly, like “Will It Go Round in Circles” and “Nothing from Nothing,” which he performed on the very first episode of “Saturday Night Live,” beaming under an Afro wig as big as his head. Yet given his gifts (keyboard virtuoso, powerful soul voice, stellar dancer, able to craft a propulsive hook), why didn’t Billy Preston become a bigger star? Who was he, exactly, as an artist? I went into the documentary fuzzy about all those things and came out feeling like I finally knew him.

That includes knowing the side of him that dragged him down. Preston, as most of those around him ultimately figured out, was gay, but he was supremely secretive and conflicted about it. Was he tormented internally, the way that Little Richard, who Preston performed on tour with in the early ‘60s, seemed to be? Little Richard was the most flamboyant closeted figure in rock history…until he abandoned music for the church…then returned to the pop sphere and came out of the closet…then went back in and denounced homosexuality…and on and on. That’s conflicted.

Preston was a mellower personality, and it’s hard to say if the relationships he kept hidden — he would show up on a private plane saying that he was traveling with his “nephew” — caused him internal stress. But he was raised, by his single mother, in the church, and he remained a church-bound figure who didn’t have it in him to declare publicly who he was. Billy Porter, interviewed in the film, discusses the history of this (“It ain’t just the choir director, honey. There’s a lot of queens in everybody’s church”), and how it just wasn’t talked about.

Preston had a musical link to the Black church that was singular in the rock world and almost primal: He played the organ — in particular the Hammond B3, a complicated instrument with multiple levels. (He was also a wizard on the Fender Rhodes.) There’s a great book to be written, or documentary to be made, about the use of organ in pop music (“A Whiter Shade of Pale,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Green Onions,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” Boston’s “Foreplay,” Blondie’s “11:59,”), and Billy Preston was the unabashed king of that instrument. Born in 1946, he began playing it in church when he was a little boy, but he quickly became a crossover phenomenon. There’s an astonishing clip of him on “The Nat King Cole Show” in 1957, where he plays a song he wrote called “Billy’s Boogie,” and his jaunty confidence is something to behold.

But here’s what’s amazing. Starting in 1963, Preston put out a series of three albums built around his organ playing. The third of them, “Wildest Organ in Town!” (1966), was a collaboration between Preston and Sly Stone, who arranged the songs but didn’t write them. One of the tracks, “Advice,” is the clear forerunner to “I Want to Take You Higher.” The inventor of funk was James Brown, and the form’s two mythical inheritor-innovators were Sly Stone and George Clinton. But the documentary makes the case that Billy Preston forged a heady chunk of the funk DNA. His influence is clear from his 1971 single “Outa-Space,” which became the prototype for a certain clavinet-driven ’70s jam (the Commodores’ song “Machine Gun,” featured in “Boogie Nights,” is just about a remake of it).

Preston achieved success and enjoyed the fruits of it, like his horse ranch in Topanga Canyon. He was worshipped by people like Mick Jagger, who showcased Preston onstage — how many people get to dance with Mick Jagger? — on the Stones’ 1975 tour. I think it’s clear, though, that if he had run his career in a different way, Preston could have been a more popular artist, perhaps the leader of a band as big as the Commodores or Kool and the Gang.

But there’s a way that his association with the mainstream rock world may have hurt him. It blurred his identity as a Black artist at a time when those categories were being rigidly enforced by the culture. (He was accused of being a sellout the way that Whitney Houston was.) The other way Preston’s identity remained blurry related to a tendency he had to hang back that was rooted in the concealing of his sexuality. Was he a sideman or a star? The only way you become a star is to chase it forcefully enough, and there was a lingering part of Preston that was more comfortable standing in the shadows.

Just when you’re think you’re watching an upbeat pop doc, the dark side of Billy Preston’s life comes crashing in. And is it ever dark. Early on, the film testifies that Billy “lost his innocence” during the 1962 tour with Little Richard, when he was just 16 (it was during that tour that Preston hung out with the Beatles at the Star-Club in Hamburg). But according to David Ritz, the eminent rock biographer who was a friend of Preston’s, he would never say a word about his childhood experiences. Did something happen between him and Little Richard? The film suggests that it might have.

And it doesn’t take much connecting of dots to surmise that whatever trauma Preston experienced as a church-bred teenager on the road with depraved rock ‘n’ rollers, it came back to haunt him in his self-destructive abuse of alcohol and cocaine. This chapter of the story barges in rather abruptly, but once it does Preston’s descent becomes tragic.

He couldn’t stay away from the cocaine — or, once it hit the scene, crack. He got into mountains of debt, owing millions in taxes. His career bottomed out in the late ’70s, when disco had evolved Black music to a place beyond Preston’s funk-based grooves. And he never had the solid domestic life that could have acted as a ballast. He became the band leader for David Brenner’s short-lived talk show, and there’s a cringe-inducing clip in which Howard Stern, a guest on the show, comes over to Preston, smells liquor on his breath, and calls him out for it, recalling that this was the man who once played with the Beatles. Preston died, at 59, in 2006, after battling kidney disease exacerbated by his drug use. Yet he left behind a trail of people who adored him. And when you behold his talent, the gentle radiance of his presence, the way he could sweep you up, and maybe toward the heavens, with one of his organ riffs, you can say without a doubt that the decline and fall of Billy Preston was not the way God planned it.

Italian

Italian