It’s a herculean task to channel Hayao Miyazaki, the Japanese animation legend behind “The Boy and the Heron” and many more. However, Pakistani production “The Glassworker” goes beyond merely aping Miyazaki’s distinctive style. It gets to the heart of the anti-war sentiment that underscores much of his work — and that of Studio Ghibli more broadly, including “Grave of the Fireflies” director Isao Takahata — resulting in a film that, like many Ghibli productions, feels at once familiar and fresh.

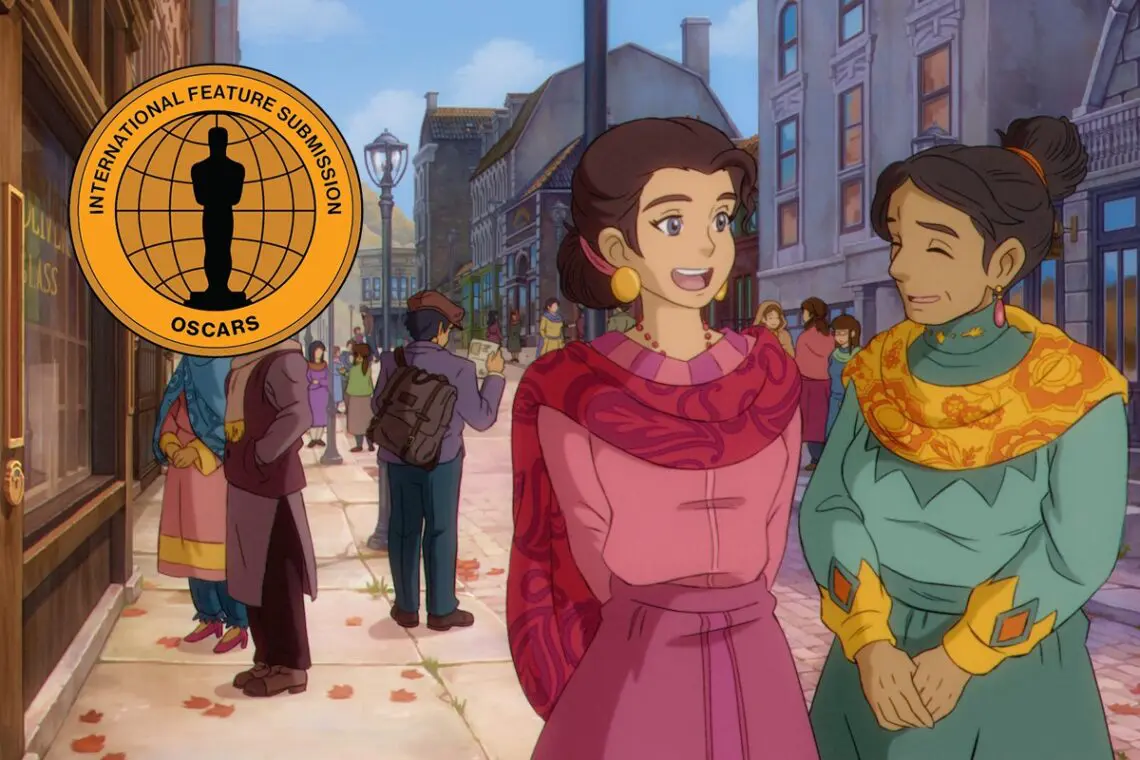

The directorial debut of Usman Riaz, “The Glassworker” is Pakistan’s first fully hand-drawn feature, crafted by Mano Animation Studios under the mentorship of Ghibli producer Geoffrey Wexler. Miyazaki’s sensibility practically runs through the movie’s veins, beginning with its setting: a vibrant early-20th-century town called Waterfront designed of a combination of European and Asian (in this case, Pakistani) influences. Its buildings are in the Dutch Renaissance style, while its characters — who are ethnically diverse, and wear both Western and South Asian Muslim garb — all speak Urdu. Moreover, the town’s quaint coziness clashes with the advent of industrialism, and the widespread manufacture of weapons of war.

Much of the story unfolds in childhood flashback, though it begins with young adult Vincent Oliver (Taimoor “Mooroo” Salahuddin) reading letters sent to him from afar by his first love and former school classmate, Alliz (Mariam Riaz Paracha). Vincent now manages the glassblowing workshop and storefront run by his father, the stern but conscientious Tomas (Khaled Anam). However, Vincent was but an adolescent apprentice (voiced by Mahum Moazzam in flashback) when he first laid eyes on the younger Alliz (still voiced by Paracha), who moved to their town when her father, the military leader Col. Amano (Ameed Riaz), was posted there to manage an oncoming war against an enemy we rarely see.

Popular on Variety The political details of “The Glassblower” are left largely vague, in part because Watertown is a fantasy hybrid of numerous cultures (set in a world where blimps reign supreme), but in part because this conflict is seen through the eyes of children. This is perhaps what is most Ghibli-esque about the film, but simplicity also aids in getting the movie’s point across. Even as its tale of innocent childhood romance moves toward greater complexity, “The Glassworker” remains unconcerned with geopolitical specifics — or even metaphors — favoring an intimate approach to the way war rankles the soul.

Glass is all-important to building the weapons in this conflict (or perhaps that’s just how Vincent remembers it, since glassworking is his world), which leads to Col. Amano seeking Tomas’ help, despite the artisan being practically outcast for being a pacifist during wartime. Riaz captures Tomas’ dilemma with aplomb, transforming it into a defining, larger-than-life event through Vincent’s eyes and the first of many ugly moments that weighs heavy on the young boy’s heart.

The film also features a supernatural subplot involving Djinn — supernatural beings of Islamic myth — who, though they remain unseen, are marked by Carmine Di Florio’s twinkling score, and reflect and refract light in Vincent’s direction, perhaps even influencing him. It’s not quite the most thought-out throughline, but it does work as an easy fix to quickly mold the slowly maturing Vincent according to the story’s whims, an inelegant journey with its own remarkable outcomes.

Despite Vincent’s own eventual pacifism, simply living in a world defined by war turns him bitter in the long run, a transformation the animators deftly capture through subtle details, like the worsening wrinkles beneath his eyes. The level of detail put into bringing the characters to life allows for a more reflective mourning on all that’s lost in war — from youthful innocence to the opportunities to better oneself (Vincent’s childhood bully ends up with a surprisingly meaningful role).

“The Glassworker” often takes its time, though in doing so, it builds toward charged and moving moments, in which its “heroes” and “villains” alike display unforeseen complexity. While it doesn’t break new ground for animation at large (despite being a landmark for Pakistan), it’s an effective homage to an industry legend that truly gets to the heart of what his movies were about.

Italian

Italian