There’s a notion in the film industry that comedies don’t travel. Jokes have a regional audience, and humor gets lost in translation, the thinking goes. But director Matthew Rankin thinks more of audiences than that. His new film, “Universal Language,” was selected by Canada as the country’s submission for the Oscars’ international feature category, but you’d be forgiven if you were unable to place it.

Set in an alternate Great White North where Tim Hortons coffee shops are Persian tea houses and the principal language is Farsi (but Quebec is still French, because of course it is), Rankin’s film gently imagines a world without cinematic borders: an absurdist but warm-hearted vision that has disoriented and delighted festival audiences since its premiere in the Director’s Fortnight section at Cannes.

“As much as we don’t think of it as a political film, there is something radical to this gesture,” Rankin says on a Zoom call. “One thing that struck us is that Canadian viewers who might have very little knowledge of Iran, and Iranian viewers that might have very little knowledge of Canada, have both said to us that they find the film makes them feel nostalgic. That’s something that we found really touching.”

Popular on Variety Rankin is calling from his native Winnipeg, seated next to his two friends and co-writers, Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati. “Universal Language” was a decade-long project for the trio, with roots tracing back to Rankin and Nemati’s time shooting “propaganda films” for Canada’s national parks. Drawing comparisons to other transnational oddities like Jim Jarmusch’s “Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai” and Takeshi Kitano’s “Brother,” the trio see their own feature in the same tradition of fusing far-flung cinematic influences.

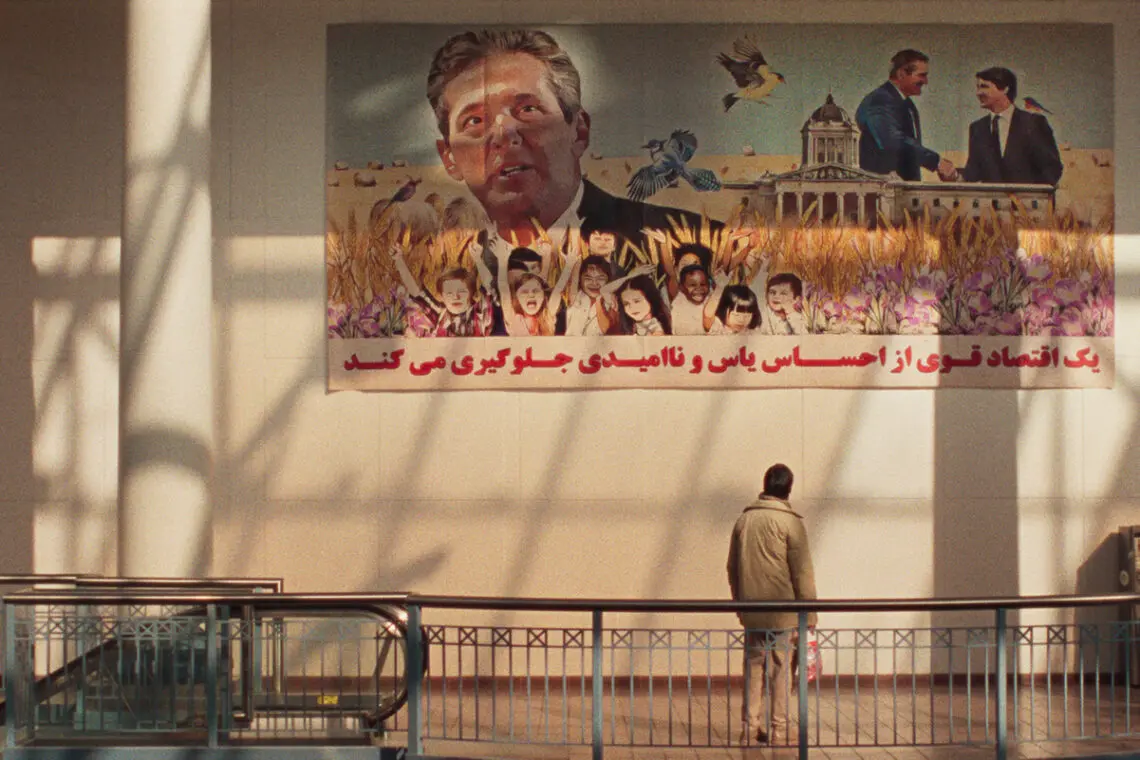

It’s a driving force for the countless sight gags of “Universal Language”: Winnipeg’s ubiquitous real estate brand Lord Rodney becomes “Rodney Khan” and a mural of Justin Trudeau is adorned with Farsi words reading “a strong economy limits feelings of worthlessness.” But beyond the humor, there’s a playful reflexivity to the entire film — an approach that Rankin and company say takes inspiration from Iranian filmmakers like Abbas Kiarostami.

“There’s an effort to remind you that there is an element of artifice at play,” Rankin says, before illustrating with a very Canadian metaphor. “In the West, the hockey game is the ultimate incarnation of how we typically shoot films. Follow the puck, wherever the action is. When it’s my turn to speak, the camera is on me. When you speak, the camera turns on you. But in a lot of these Iranian films, the person listening is more interesting than the person who’s speaking.”

On the Winnipeg set of “Universal Language” Maryse Boyce “It does take some acclimatization, but once you catch the rhythm and absurdity it leads you somewhere,” Rankin continues. “And it’s always interesting when people do catch it. Not everybody does at the same spot.”

And as Kiarostami would occasionally appear in his own movies, Rankin does as well here, putting some autobiographical skin in the game. Firouzabadi and Nemati insisted that the director play the scripted version of himself, whose arc involves a Winnipeg homecoming to visit his mother. It’s a particularly painful storyline; Rankin’s own parents died during the height of the COVID pandemic.

“It’s a very vulnerable place to be, but it could not have been anybody else,” Nemati says. “Acting is already so difficult, but acting in a different language that is your own — it’s another level.”

“That’s the first time you say that,” Rankin says with a laugh. “I was cast when everyone else was cast. I was trying to give myself a break by entertaining the notion that some other actor could play me better than me. But we determined that the theme would be more energized if it’s really me playing this fraudulent version of myself. Even the idea that I might be badly cast playing myself was something that I found to be funny.”

Matthew Rankin on the set of “Universal Language” Courtesy of Oscilloscope Rankin was hardly the only newcomer to screen acting. Nemati plays a Winnipeg tour guide, a profession Rankin’s father once held. And Firouzabadi appears as a punk bus driver. Much of the cast is populated by their loved ones, who they found to be camera-ready in their own ways.

“What we discovered was teachers are amazing performers,” Nemati says. “They’re performing in front of a class all the time.”

“These are our family, our community, our friends who are in it,” Firouzabadi says, going on to discuss how two young characters went from being scripted as a boy and girl to two sisters in the final film. “In Farsi, we don’t have ‘she’ and ‘he’. We have just او (“ooo”) — it means them. This movie for us, when we’re talking about it and the process of the writing for us, was something exactly like ‘ooo.’”

“As much as it’s surreal, I feel like it’s actually a very realistic depiction of our lives,” Rankin says. “The blending of codes and realities — that’s part of all of us. As much as the world might like to organize itself into rigid, sealed-off Tupperware containers, our lives together are infinitely more fluid than that.”

Speaking of “gender-neutral casting,” Danielle Fichaud makes a big impression early on in the film, growling as a Quebecois bureaucrat in drag. I found her scene to be a tuning-fork for the absurdist tone of the film. How did her casting come about? RANKIN: She is a brilliant actor. She was in this movie called “Aline,” where she plays Celine Dion’s mother and she was just spectacular. She was my acting teacher a long time ago and she just absolutely fascinated me. She always used a lot of very sexual language in all of her directing. She’s got a very dirty mind, in the best way. She’s a beloved actor in Quebec. There was no other person that we had in mind for that part.

A Quebecois bureaucrat (Danielle Fichaud) blasts Matthew Rankin (Matthew Rankin) in “Universal Language” Oscilloscope The film has such a cohesive style for an on-location production. It’s no surprise you’ve cited Jacques Tati as an inspiration. Could you discuss finding locations in Winnipeg that squared into the sharp visual design you conceived of? RANKIN: I believe the mall in the film is about to be demolished. If I recall correctly, in the script, the fountain in it was going to launch. But then they told us that it was a $10,000 fix to repair to make that happen. The nature of the scene kind of changed because of reality. And then, the zigzag staircase building — there are several buildings like that in Winnipeg, but getting access to them was almost impossible. In fact, we got access to that one only a half-hour before we were supposed to shoot.

NEMATI: We did a few takes. The last one where everything went well — the moment you reach the top of the stairs, there were two girls who came out of the apartment. So we… kept quiet.

RANKIN: They were ready to go clubbing. But that was our little tribute to “Where Is the Friend’s House?” The zigzag staircase.

Matthew, I’ve read you expressing frustration with contemporary cinema and how it can feel siphoned off into different genres and cultures. Can you expand on how that belief squares with “Universal Language”? RANKIN: I’m skeptical of cinema as a simulacrum, which the arc of film history is bent very much towards. Silent film to sound film, black and white to color, E.T. being played by a puppet to being corrected digitally by Steven Spielberg to make it more realistic — the arc is towards making cinema as credible as possible. But when we embrace the artifice of cinema, it actually opens up new expressive possibilities, new ways of making images that normally we have resisted. My feeling is the space of the simulacrum is migrating into AI and video games and virtual reality. That actually opens up new ways of image-making. It’s kind of like what happened to painting when the photograph was invented. Painting was no longer imprisoned. The purpose of paint was not to imitate reality as perfectly as possible. We can sort of acknowledge that it’s paint and there’s new modes that get explored. I feel like the same thing will happen to cinema. That’s part of the strategy at work here: defying the simulacrum and finding new things to be said that it can’t. It’s Iranian poetic cinema with Winnipeg surrealism and Quebecois melancholy. But in my heart, that crossover is a reflection of how we live together.

Italian

Italian